"Creation as a Reflection of Self"

| None | Light | Moderate | Heavy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language | ||||

| Violence | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Nudity |

What You Need To Know:

CQ is a playful movie that's lots of fun. Writer/Director Roman Coppola has obviously observed and collected his own real-life filmmaking experiences and written them into the script. One message that shines through loud and clear in CQ is that art is inherently a reflection of the creator’s life. Hebrews 11:3 states that, “what is seen was made from what is unseen.” What is seen on the screen comes from the unseen experiences, hearts and minds of the filmmakers. Regrettably, there is plenty of sensuality and some nudity in this movie. Also, a horoscope is read and a woman begins yoga-styled meditation. Moral viewers therefore should exercise extreme caution.

Content:

(B, Ho, O, Pa, So, L, V, SS, NN, A, D, M) Metaphorical view of art as a reflection of the creator or artist with a horoscope read, a woman begins yoga styled meditation, and a romantic socialist revolutionary; rare and scattered use of a few profanities, curses and obscenities, plus urinating; fired director punches through door in anger, some purposely cheesy 60s science fiction/spy karate violence and laser beams, depicted auto crash with no injuries, and implied auto crash with driver shown later on crutches; brief artsy black and white film clip of nude girlfriend in bed, implied homosexuality as one of the sci-fi actors talks to the director in bathroom while he’s urinating (no nudity) then turns to find that his date (a man) has been looking for him everywhere, woman rolling around in satin sheets showing plenty of skin (nudity implied), man and woman roll around in comedic high-speed, James Bond-like implied fornication scene (nudity implied), and character’s father tells him that he hasn’t always been faithful to mom; 1960s style bikini, girl’s thong-clad derriere briefly shown as her skirt flies up while climbing into a car, extreme long shot of silhouette of nude woman in window while changing, brief spoof of a B-grade stylized sexy vampire movie with women in low-cut dresses or gowns (noticeably no bras); alcohol use at parties; opium den like scene in 60s style commune; and, cohabitation.

More Detail:

CQ is lots of fun. Roman Coppola has created an imaginative and delightful satire that juxtaposes two very different genres of filmmaking and shows us that inevitably, no matter what genre, some part of an artist’s life is reflected through his work, sort of like Romans 1:20 in the Bible.

Roman has obviously observed and collected his own real-life filmmaking experiences and written them into the script. Being the son of Francis Ford Coppola and participating in the production process has exposed him not only to the skills necessary to have produced this fun look at the filmmaking process, but has surely given him enough anecdotes to fill dozens of movies illustrating the different personas and sensibilities that make up the creative process.

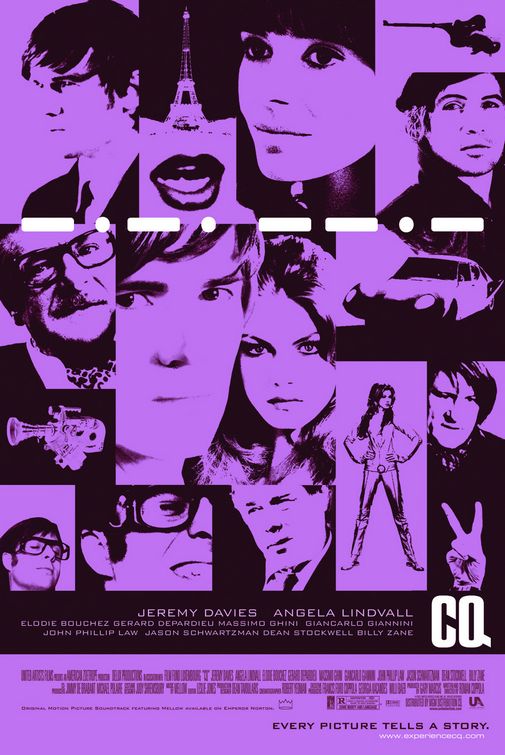

Set in Paris during the turbulent late 1960s, CQ tells the story of a young American filmmaker, Paul (Jeremy Davies), who is editing a sci-fi B-movie entitled DRAGONFLY. The title character, played by supermodel Angela Lindvall, is a beautiful wonder spy who is a cross between Barbarella and James Bond.

After work, in the evenings, Paul shoots his own movie that is supposed to be an honest journal of his own real life (a la the 1968 movie DAVID HOLZMAN’S DIARY). Except the poor guy can’t figure out who he is. Several times, he exclaims his dilemma to either careless or helpless listeners. Even the critically observant musings in his daydreams urge him to “connect things . . . make us feel something.”

His Parisian girlfriend, Marlene (Elodie Bouchez), moves from jealous to angry to out, as Paul’s obsession with finding himself through film evicts her from his life. She tells Paul that “filming everything in your life won’t make you understand yourself better.” The last straw for her is when Paul buys a new camera and it is delivered to their shared apartment. When he opens the box to remove his new treasure, Marlene points out that he has invested all his money and time into his movie and none in his relationship with her.

The situation worsens as the artsy director of the movie, passionately played by Gerard Depardieu, is fired because he has become obsessed with the fictional character of Dragonfly. Rather than making a profitable commercial movie, he wants to “auteur” a socialist revolutionary statement. He firmly believes, “Film can change the course of the future.” The producer (Giancarlo Giannini) would be satisfied with a B-movie that ends with a bang and a twist.

The director who is hired in his place is a mod, arrogant, immature brat. He is more into the glamorous benefits of being a director – girls, girls, girls – than he is into finishing the movie. He too eventually loses his position.

The producer, out of desperation, chooses the faithful editor, Paul, to direct the finish of the movie since he has been with them from the beginning. The producer finds encouragement in the fact that Paul is working on his own personal movie and trusts that he will be able to wrap things up.

Now, Paul’s added dilemma is just how to end the twice-orphaned movie? As his reality teeters from the inherent dishonesty of his own film “journal,” because he doesn’t really know who he is, to the fantasy world of a sci-fi flick, Paul too falls in love with both the unassuming actress who plays the fantasy role of Dragonfly and her character.

Rather than finding answers in fantasy conversations with his muses and the character of Dragonfly as he racks his brain for ideas, it is only by being an observer of his real-life experiences that he discovers a little bit of himself, and, by applying creativity, the perfect ending to the movie.

One of the events he finds inspiration in is a meeting he has with his father who is laid over at a local airport for an hour on Christmas Eve. They have a catch-up conversation and his father mentions a strange phenomenon. Sometimes, while traveling, he thinks he sees Paul, or maybe Paul’s unknown brother. He says it’s possible that Paul has siblings he doesn’t know, “because you know I haven’t always been faithful to your mom.” Later in the movie, Paul has an experience like his father’s when he seems to see himself (or maybe his brother?) drive past himself but with beatnik facial hair and beret.

Another event is a confrontation Paul has with the film’s original director in some riverside tunnels at night. The director comes out of the shadows to try to persuade Paul not to ruin his original vision for Dragonfly because he is still passionately consumed by the project.

These two sets of events are not explicitly portrayed in Paul’s rendering of the end of Dragonfly, but they are very obviously drawn on as inspiration in the final scene. It seems that there is more of Paul’s life reflected in the final 15 minutes of DRAGONFLY than in his daily sittings for his own personal film project. One message that shines through loud and clear in CQ is that art is inherently a reflection of the creator’s life. Hebrews 11:3 states that, “what is seen was made from what is unseen.” What we see on the screen in CQ comes from the unseen experiences, hearts and minds of the filmmakers.

There is, however, plenty of sensuality and some nudity in this movie. Moral viewers therefore should exercise extreme caution.

- Content:

- Content: